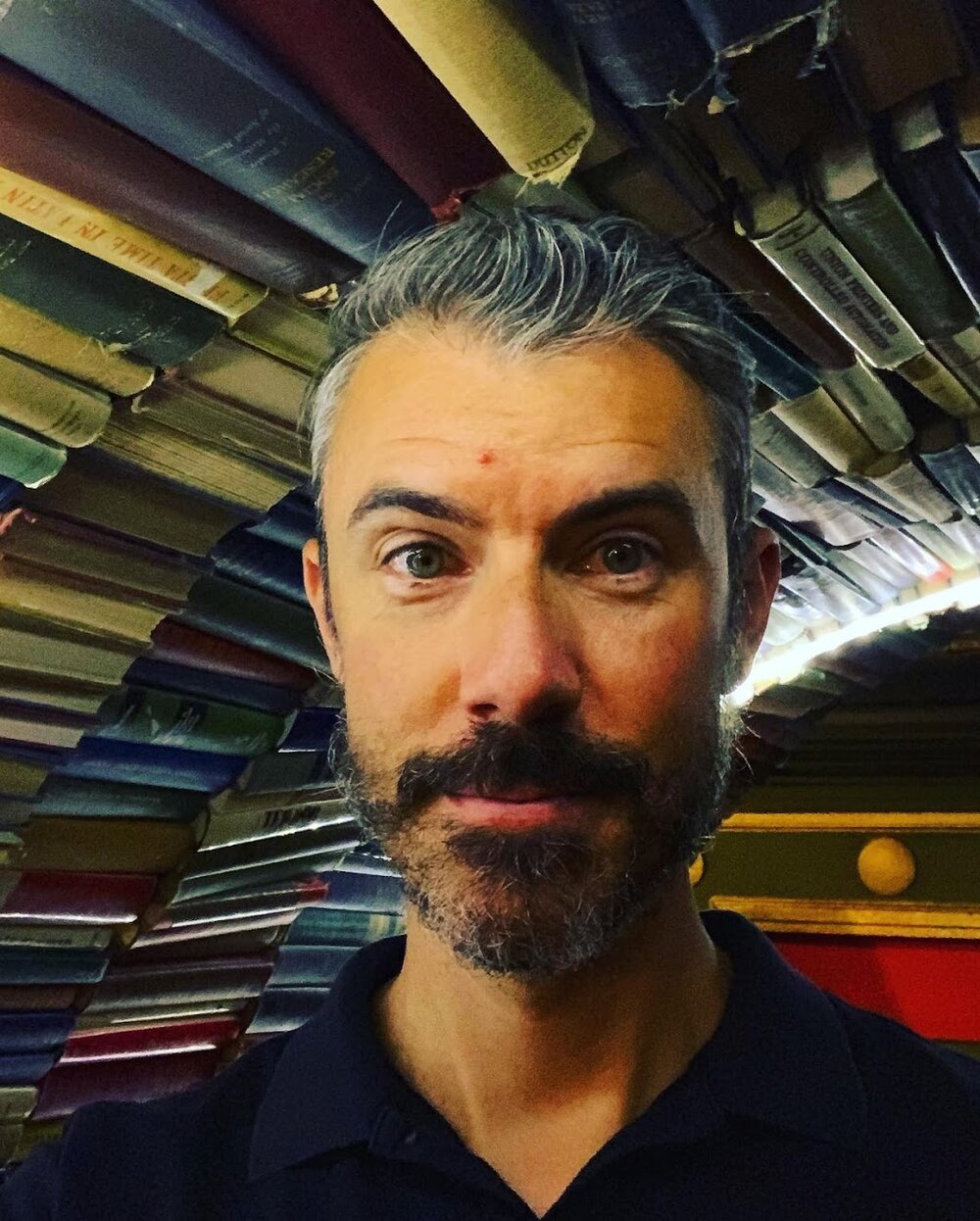

Chris Holmes

PhD, 2012

Associate Professor and Chair of Literatures in English

Ithaca College

What did you think you wanted to do post-graduation when you began the English PhD program here at Brown? Did that change during your time in the program, and if so, how?

For the first few years of the program, I imagined that I would be happiest at an R1 university where I would oversee graduate students and have significant research support. My goals and aspirations changed as the 2008 housing market crash wiped out what was already an anemic job market. Brown went from sending just about every one of its graduate students off to tenure-track employment in 2005 and 2006, to struggling to place any of its graduates in TT jobs, while hoping and praying for postdocs in 2008, 09, 10, and 11. It was a particular grim moment for jobseekers. By the time I was ready to graduate, I wanted a job, preferably one that didn’t have a 4/4 teaching load and/or expectations of coaching the squash team.

How would you describe your PhD project? Who was on your committee? If you went on the academic job market, what fields (including but not limited to those in English) did you apply under (ie. 20th Century Studies, Gender Studies, Poetics, etc.)?

In the beginning stages of writing, I thought of my dissertation as a postcolonial project. Later I would realize that it was very much a world literature project, with a particular interest in form and the contemporary novel as understood through a handful of major (with a sprinkling of very minor) Anglophone writers.

My committee was Professors Kunle George, Rey Chow, Ravit Reichman, and Paul Armstrong. I received consistently wonderful advice from my committee about the project, the book, and the job market. Picking the right committee is paramount.

I applied for world literature, postcolonial, 20/21st century, and British/Anglophone jobs. I ended up being a candidate for several British Literature jobs, which is hysterical, as I had/have very little understanding of the history of that field, beyond the implications of Empire on the production of British Literature. Tim Bewes will probably remember hosting a mock MLA interview for me during which I struggled to list five 20th century British writers who would make up a theoretical syllabus for this position. I mean, I know five British writers, but the pressure to understand why a particular five would stand in for the tradition of British literature was too much for me. The job I have now is loosely understood as a contemporary world literatures position.

What kind of work are you doing now? Can you tell us about your path to this career? How did you get started?

By dumb luck I got at tenure-track job my first year on the market. You must keep that in mind: Brown will get you in the mix, but from there it is 75% luck. I’ve hired five colleagues since I began at Ithaca. They are all brilliant, but the gradations between finalists are small indeed.

My job hunt story is interesting, but not at all unique. I had just been rejected after a campus interview for a plum job in Virginia, and I was planning on signing a contract to start as a lecturer for the History and Literature Program at Harvard, when I was invited for a last-minute campus interview at Ithaca College. Ithaca wasn’t on my radar, as they had written me after MLA to say that I wouldn’t be coming to campus for an interview. However, in the weeks that had passed, their top candidate had taken a different job, and they were looking for three new candidates. The turnaround time for preparation was very short. I had perhaps a week to write a new job-talk and prepare a model lesson. I spent the three days on campus in a fugue state, but came out of it with a great job, on a sane and collegial faculty. I credit my mom entirely, who compelled me to write Ithaca a letter of thanks after they initially told me I wouldn’t be a finalist. Thanks, Mom.

What is your favorite part of this work? What has been the biggest surprise?

My favorite part is that the job evolves. The probationary period before tenure is frantic— every article, every bit of service, and every student evaluation feels like it will make or break your career. This isn’t true, of course, but the high stakes nature of the pre-tenure years is no joke. Think the dread you felt watching Man on Wire, only you can no longer turn off the movie.

After tenure, you get to apportion your work hours more equitably and to the areas that you care most about. I now write with more ease and in forums that I admire. I have time to edit special issues, write book reviews, and, most joyously, start a podcast (burnedbybooks.com). I love teaching the students at Ithaca. My word of warning is that a 3/3 teaching load or higher makes writing during the semester more of a fever dream than a pleasure.

One of the big joys and surprises of a small college job is that they are desperate for you to invent co-curricular activities. I was lucky enough to meet the novelist Eleanor Henderson—who teaches in the creative writing program—early on in my days at Ithaca. Together we conjured the idea of a Michael Chabon’s WordFest-style literature festival that could be an annual event at the college. The result, The New Voices Festival, just finished its 10th anniversary celebration. Don’t be afraid to invent the things you wish existed on your campus. Ask forgiveness, rather than permission.

Which resources (at Brown and beyond) were most helpful to you in your specific career path?

The Sheridan Center was my primary source for professionalization at Brown. They were enormously helpful both with pedagogical growth, and the small-scale logistics of getting on the market. I found them welcoming and supportive.

What advice do you have for students currently enrolled in this program, as they plan for their futures?

Fields are slippery and porous. Work with your committee to make sure that your project can be positioned in several fields. Depending on the fluctuations of the job market when you first go out, you can position yourself for different kinds of jobs. Don’t get hung up on needing to be an expert in a field or subfield of jobs to which you are applying. For most jobs, observing strict field boundaries disappears the moment you start the position.

Your colleagues are your greatest resource at Brown. Obviously, your professors are incredibly important, but when you leave Brown, it’s your peers who will support you through the difficult times. They will read your writing, brainstorm syllabi, commiserate about faculty meetings and terrible colleagues, and they will help you explain to your parents why just because they think you’re a swell guy doesn’t mean that you can “go get a job at Princeton”. Keep your friends close.